Exploring the far North on a photographic expedition offers a unique perspective on one of the most remote destinations in the world. Monday, 2 December 2019

The dramatic cliff-faces of Alkefjellet are home to thousands of sea birds. Photograph by Jamie Lafferty.

Boomer Jerritt is a very patient man. As One Ocean Expeditionsʼ assigned photographer-in-residence for the companyʼs Spitsbergen Encounter programme, he must exude this calm in the face of man and beast alike. The former is almost always a bigger challenge.

Over the course of 10 days sailing around Svalbard aboard the Akademik Vavilov in the unyielding light of summer, I follow Boomer closely, learning everything I can about photography from this award-winning master. I have some pretty decent kit with me, but my experience is nothing compared to the man from British Colombia.

However, while I attend his on-board lectures and ask him questions each time we disembark, he makes himself available for all passengers, whether theyʼre a semi-pro carrying thousands of pounds of equipment or an iPad- wielding granddad. Whatever our respective levels, itʼs hard not to want to show off any good photos to Boomer, too. One way or another, he doesnʼt have much time for himself.

When it comes to photographing Arctic fauna, his patience is an example to the rest of us, especially on how not to disturb an animal when youʼre hoping to take its portrait. Here, in the High Arctic, this is much trickier than it is at the other end of the planet.

“Pretty different compared to Antarctica, isnʼt it?” says Jerritt when an Arctic fox dashes away from a couple of Australian photographers making their first venture north. Iʼm one of the lucky ones whoʼs also been to what Boomer and the other expedition staff refer to as ‘down southʼ, and his comment rings very true.

While there are dozens of similarities with the respective ends of the Earth, here in the Norwegian Arctic the animals are far more skittish and elusive — and therefore harder to shoot — than their southern equivalents. The reason for this comes in the hulking great form of ursus maritimus, the polar bear.

The presence of the worldʼs largest land predator isnʼt just on our minds, itʼs also on the minds of every creature on the archipelago. While the bears have become something of a symbol of our failure to combat climate change, an icon of fragility, up here theyʼre still a ferocious apex predator.

As a result, almost nothing hangs around too long. This means taking far fewer shots than in Antarctica, but cherishing the good ones all the more.

On our first real landing in Bellsund, we find plenty of reindeer, but off to the side, I find myself alone with an Arctic fox sporting his mottled summer colours. Following Boomerʼs advice, I get gradually closer to this wicked little scavenger, taking more and more photos, never making too much eye contact, all the while trying to suppress my jangling nerves. This lasts right up until the moment another passenger steps forward with his iPhone and scares the fox away.

Human factors aside, there are concerns when shooting in cold climates like this. The first is physical — not just feeling chilly, but the difficulties of operating a camera with exposed fingers. Even in the Arctic summer, the temperature can easily drop below zero, decreasing dexterity with every degree.

The other major problem is technical — as Boomer puts it: “The cold eats batteries.” Or at least drains them at an accelerated rate. As a result of this, weʼre encouraged to charge every night and to carry as many spares as possible. The same goes for memory cards.

As the trip progresses, weʼre fortunate to have largely good weather. By the time we get round to Alkefjellet, itʼs overcast, but that only seems to add to the drama of these sensational, Mordorian sea cliffs. Tens of thousands of auks and gulls have made this foreboding place their home. Consequently, so many black dots flash overhead that Iʼm reminded of a faulty old television.

The fast-flying birds make for an entirely different type of photographic challenge and luck plays a big part in capturing an image of any of them in flight. Of the hundreds of shots I take, embarrassingly few are remotely sharp. Thankfully, the lessons learned here come in handy later, when herds of walrus swim around our rigid inflatable boats, and again when the Akademik Vavilov is escorted into a fjord by a pod of beluga whale, their white bodies darting alongside the ship like the ghosts of dolphins.

The following day, the never-setting summer sun is blindingly bright. As we venture deep into Palanderbukta fjord, expedition leader Boris Wise orders the ship to sail as slowly as possible. Initially, I think itʼs so we can all try to shoot vast panoramas of the mind-bending clouds and mountains reflected in the still Arctic waters. Moments later, however, weʼre told thereʼs a polar bear on a huge piece of ice blocking our path. Ordinarily, an announcement such as this would come over the shipʼs loudspeakers, but so as not to disturb the bear, the message is passed around in whispers.

There are two cubs on this colossal piece of ice, too, but theyʼre so distant from the ship they can only be seen through a telescope. The mother has apparently ordered them away while she lies over a breathing hole, hoping for a seal (ringed seals are the most common prey for Svalbardʼs polar bears) to make what would likely be a final appearance above the surface.

Hours pass like this: us watching the polar bear watch the water. A sort of polar lunacy seems to take hold of the shipʼs snappers, with thousands of photographs taken of the same thing: a big bear doing nothing. “You wanted to be wildlife photographers? Well, this is it folks,” says Boomer, sotto voce in order not to affect this timeless scene.

Over our communal meals, passengers aboard One Oceansʼ Akademik Vavilov claim different motivations for coming on the trip. Some are celebrating birthdays and anniversaries, others simply want to see the midnight sun. For the photographers, there are many potential prizes, but when pushed most concede that clear shots of polar bears are the real goal.

This perhaps explains the fixation with the ice hole bear, who, after six chilly hours, finally shows us her considerable backside and disappears into the white beyond.

It certainly justifies our giddy excitement the following day when, aboard rigid inflatable boats off the frozen shores of Nordaustlandet, expedition leader Boris stumbles across a huge bear calmly striding along an icy beach.

The radio call goes out and soon all our motorised dinghies have congregated on this one, confident bear, a male who doesnʼt seem interested in eating us, but is quite content to have his portrait taken. Each mighty yawn is met with a deluge of high-end camera shutters pattering like a hailstorm.

Iʼm not the only one getting these shots, and Iʼm happy to admit this is what I came for. These are the images Iʼll want to show off to friends and family for months or even years to come. Still, as the memory cards start to fill, I remember a final piece of advice from Boomer: to put down the lens for a moment and, with my naked eyes, take in the magnificence of the experience.

When we get back to the ship, the other passengers seem delighted on my behalf. Iʼve evidently spent a little too much of the cruise saying how excited Iʼd be to get close to the bears. I order a beer, salute Boomer, and retreat to my cabin to admire my own work.

Then something strange happens: I put the wrong memory card into my computer. There are no photos. I chastise my idiocy and put the other card in. Nothing. Both cards are reading as empty. I have no photographs of any bears. Not even an iceberg.

Over the loudspeaker, Boris summons all passengers for lunch. My appetite has left me though — in its place I have a feeling that either makes me want to cry or vomit or both. Trembling, I make my way to lunch.

I must be as white as the bears themselves because as soon as I sit down Iʼm asked if Iʼm OK by Lauren Shipton, the only British expedition staff member on board. Confident of both her kindness and discretion, I explain over the salad bar whatʼs happened, but I can tell from her widening eyes that this is a disaster.

Miraculously, Robbie Krysl, a young Canadian student and enthusiastic photographer, overhears and offers use of his recovery software. Feeling like an old Luddite, I hand my cards over to the teenager straight after lunch.

No one, not even Boomer Jerritt, has any idea how my nightmare has happened, but a couple of hours later Iʼm on the brink of crying with gratitude when Robbie shows me my recovered photos. In that moment, polar bears never felt more precious — nor more endangered.

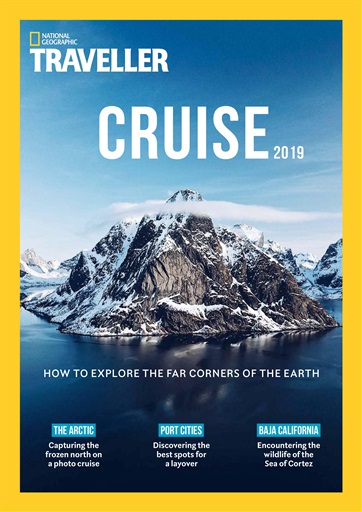

Published in the National Geographic Traveller (UK) Cruise guide 2019